On a train trip west, paleo sleuth O.C. Marsh made a stop in Nebraska that changed his career and upended previous notions about the evolution of the horse. Learn about this pivotal find, its implications, and the brilliant scientist who spied paleontological gold in dirt from a well.

The Union Pacific whistle stop called Antelope Station (that has now grown to become Kimball, Nebraska) is remembered as the scene of dramatic discoveries that changed the life of O.C. Marsh and the course of North American paleontology.

Here is Marsh’s own account of his trip to Antelope Station, where he had been told human remains had been dug up in the course of excavating a well:

“It was my first visit to the far West, and all was new and strange... Before we approached the small station where the alleged primitive man had been unearthed, I made friends with our conductor, and persuaded him to hold the train long enough for me to glance over the earth thrown out of this well, thinking perchance that I might thus find some fragments, at least, of our early ancestor. In one respect, I succeeded beyond my wildest hopes. By rapid search over the huge mound of earth, I soon found many fragments and a number of entire bones, not of man, but of horses, diminutive indeed, but true equine ancestors... But the horse was not alone. Other fragments told of his contemporaries—a camel, a pig, and a turtle at least.”

“Recalling the old adage that 'truth lies hidden in the bottom of a well,' I could only wonder, if such scientific truths as I had now obtained were concealed in a single well, what untold treasure must there be in the whole Rocky Mountain region. This thought promised rich rewards to the enthusiastic explorer in this new field, and thus my own life work seemed laid out before me.”

In 1879, Marsh’s work on fossil horses as well as the Cretaceous toothed birds of Kansas prompted a letter from Charles Darwin praising Marsh's work as one of the best illustrations of evolution since Darwin’s own book, On the Origin of Species. Marsh was one of the first American scientists to embrace Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

O.C. Marsh contributed greatly to our understanding of horse evolution and our knowledge of long-extinct creatures like the Brontothere.

O.C. Marsh found fragmentary remains of ancient horses and other fossil mammals at Antelope Station. The specimens he collected, the exposed geology he saw as he traveled farther west, and the “hatful of bones” given to him by the station agent on the way home excited Marsh so much that he arranged for a series of four Yale expeditions to gather more. In 1870, 1871, 1872, and 1873, Marsh traveled with students into the fields of the West to collect fossils. One of his finds was the first American pterosaur fossil in 1871.

Marsh made a series of fossil horse discoveries, collecting 600 specimens in Nebraska's White River Badlands and Niobrara Valley, along with a few significant fossils in Wyoming from the oldest of horse species that led him to propose a whole new line of descent for the horse family. Before Marsh’s work, the accepted belief was that horses were absent to America until introduced by Spanish explorers. Marsh also made many brontothere discoveries in Nebraska and Dakota and published important papers about his finds.

After those initial trips into the field, Marsh did the remainder of his work at Yale, studying specimens shipped back to him by hired crews. He developed theories that have gained acceptance today, including the idea that birds evolved from dinosaurs. He identified dozens and dozens of species and reconstructed skeletons, amassing collections of fossils used by many generations of paleontologists to better understand the evolutionary process and the ancient history of vertebrate life on Earth.

Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857-1935) was the first curator of the Vertebrate Paleontology department at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He was one of several paleontologists who built on Marsh’s work to arrive at an understanding of horse evolution in the New World.

Osborn had a very broad expertise in vertebrate paleontology. He synthesized research into highly valued publications including The Age of Mammals in Europe, Asia, and North America (1910); and The Titanotheres of Ancient Wyoming, Dakota and Nebraska (1929). His extensive studies of fossil horse collections, many specimens of which were collected by Marsh, led to his ground-breaking monograph on horses, Equidae of the Oligocene, Miocene and Pliocene of North America published in 1918.

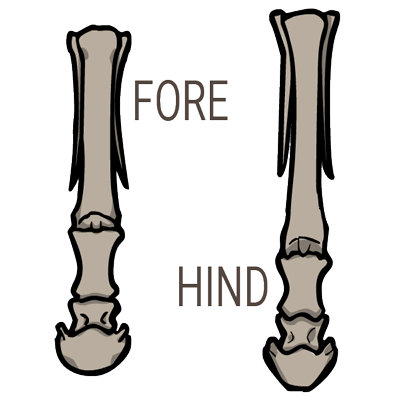

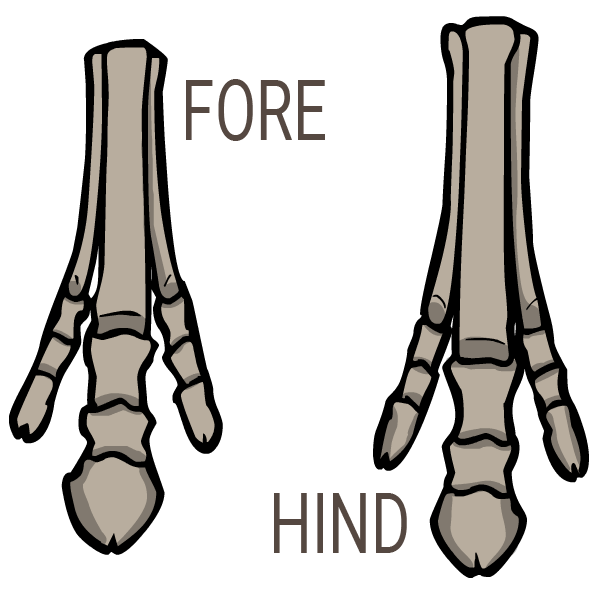

Fore foot and hind foot

Epoch: Eocene

Each of these fossils is from an ancient relative of Equus, the modern horse.

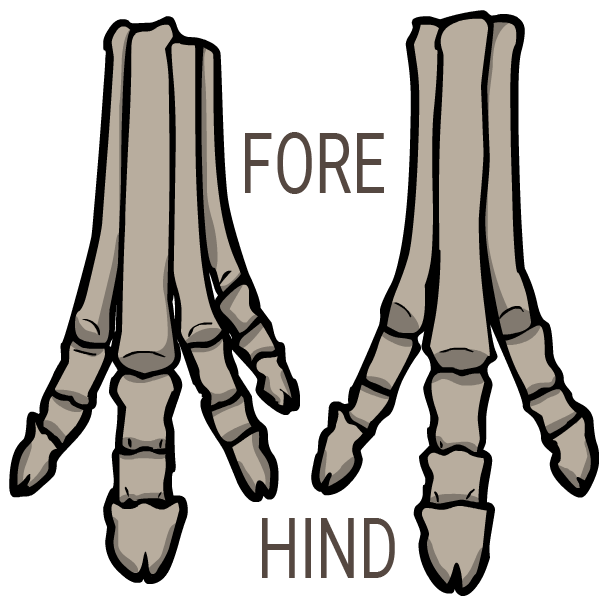

Fore foot and hind foot

Epoch: Miocene

Each of these fossils is from an ancient relative of Equus, the modern horse.

(Anchitherium)

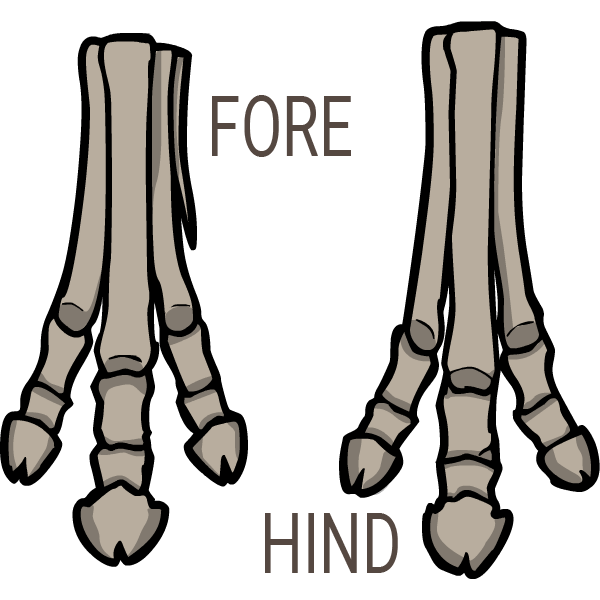

Fore foot and hind foot

Epoch: Miocene

Each of these fossils is from an ancient relative of Equus, the modern horse.

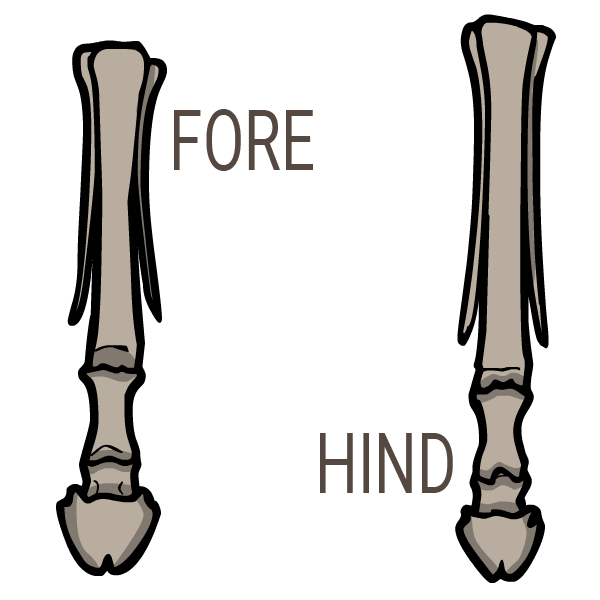

(Hipparion)

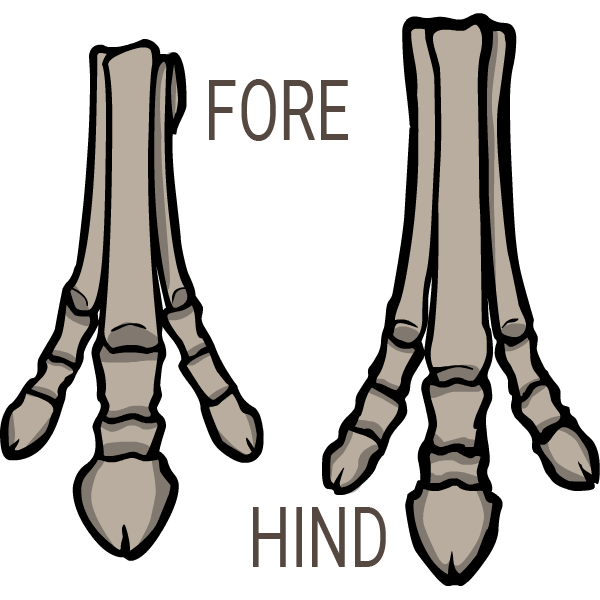

Fore foot and hind foot

Epoch: Pliocene

Each of these fossils is from an ancient relative of Equus, the modern horse.

Fore foot and hind foot

Epoch: Pliocene

Each of these fossils is from an ancient relative of Equus, the modern horse.

O. C. Marsh was the nephew of the philanthropist George Peabody. Peabody supported Marsh’s studies at Yale. Later, when Peabody was making decisions about which worthy causes would benefit from his vast wealth, Marsh convinced him to make Yale one of his beneficiaries. A gift of $150,000 from Peabody enabled the school to create the Peabody Museum of Natural History in 1866. Marsh was one of the museum's first curators, and he also served as its unofficial director. Later, Marsh made his own gift to Yale: his vast collections of fossils, specimens, and anthropological and ethnological artifacts.

The Yale Peabody Museum is the home of remarkable murals painted by Rudolph F. Zallinger depicting millions of years of evolution in the lives of reptiles and the lives of mammals.