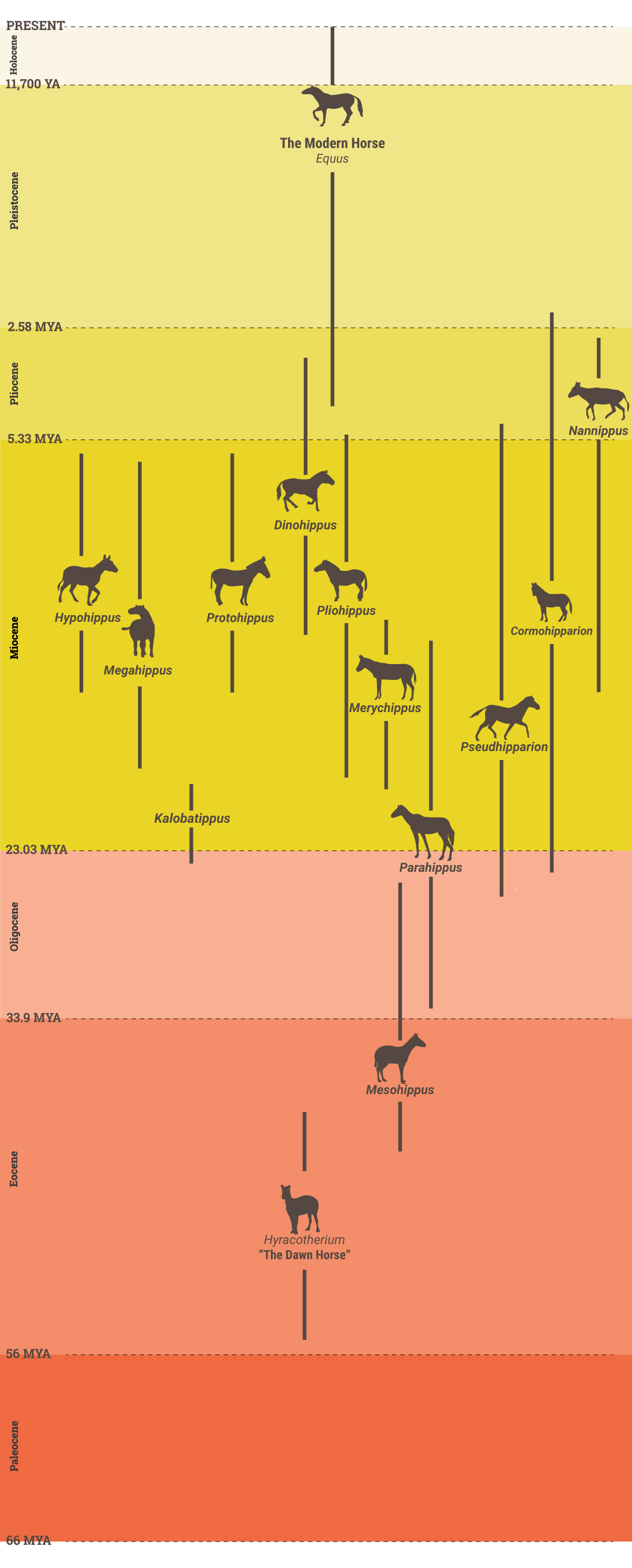

It's common to think life forms evolve in neat, connected stages, progressing from one variation to the next in an orderly ladder that leads from the original ancestor to its present-day counterpart.

But sometimes the family tree turns out to be more of a bush, with branches that end relatively quickly, or develop in similar ways without being connected.

Thanks to the work of generations of paleo sleuths and the fossils they’ve uncovered, we now know that horses have undergone this less-than-orderly style of evolution.

Horses began as leaf-eaters, with four toes on the forefoot and three on the hindfoot, and were as small as a Siamese cat. Now, they live as single-toed, long-legged grass-eaters that could easily outrun their ancestors.

See how the ancestral horse lines evolved in sometimes-parallel lines of browsers and grazers who grew steadily taller and faster to become today’s horse.

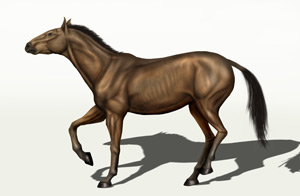

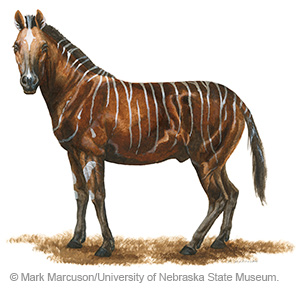

The Modern Horse Equus

4 MYA - Recent

“The Modern Horse”” species of Equus are present: horses, zebras, and asses. Many of today's horses are bigger, stronger, and faster than their ancestors due to human breeding.

Nannippus

13-3 MYA

A small, slender build grass eater was also called the “New immigrant.”

Dinohippus

10.3-3.6 MYA

The name means “terrible horse,” but it wasn’t fierce or even very big (about five feet tall, weighing 740 pounds).

It was originally thought to be one-toed, but a 1981 fossil discovery in Nebraska showed some were three-toed.

Like the modern horse, it had the ability to stand for long time periods because of the arrangement of its leg bones and tendons.

It had slight facial fossa, a primitive trait and ate grass. A close relative to Equus, the modern horse.

Pseudhipparion

26-5 MYA

Also known as “small three-toed horse” it was about the size of a large dog.

This horse had well-developed side hooves that were good for traction on soft ground and quick turns.

The name Pseudhipparion refers to its false resemblance to the Hipparion, though it was actually on its own evolutionary path,

becoming smaller rather than larger.

Specimens found at Ashfall Fossil Beds.

Pliohippus

17-5 MYA

The Pliohippus also called “Stout One-toed Horse” was the size of a white tail deer.

It was thought to have lived in social herds and considered the last “missing link” in horse evolution.

Because it showed the transition from three toes to one toe with vestigial (leftover) side toes.

Specimens found at Ashfall Fossil Beds.

Cormohipparion

24-2 MYA

A three-toed Grass eater, or mixed grass and leaf feeder also called “Sturdy, Three-Toed Horse.”

It had a deep pocket in the skull and grinding teeth with a complicated enamel pattern to better grind grass to make it easier to digest.

Specimens found at Ashfall Fossil Beds.

Megahippus

20-7.5 MYA

Known as a three-toed leaf eater it was a rare species so it’s fossils are very difficult to discover and lived primarily on leaves.

Hypohippus

17-11 MYA

Hypohippus was a three-toed leaf eater. Its name translates as “below horse” and was the size of a pony.

It had short-crowned grinding teeth with strong roots for eating leaves and chewing strong roots. Its head had a short muzzle with eyes farther forward than eyes of a grazing horse.

Specimens found at Ashfall Fossil Beds.

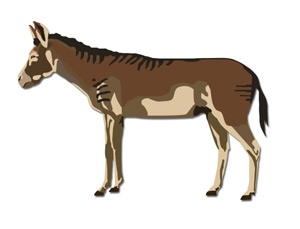

Protohippus

14-6 MYA

Protohippus was a three-toed grazer or mixed feeder.

Its name means “the very first horse,” but it was not the really the first.

It was also know as “Slender, Grass-clipping horse.” Smooth faced like a modern horse it was about the size of a modern donkey.

This horse had front teeth in a straight line that were good for clipping grass at ground level. It fed on grasses and leaves.

Specimens found at Ashfall Fossil Beds.

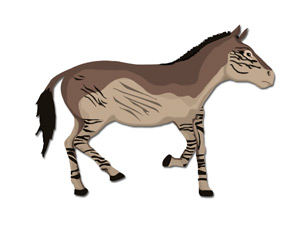

Merychippus

17-11 MYA

Three-toed with long legs, Merychippus was first high-crowned horse with tall teeth.

It had wider molars than its predecessors with strong crests on teeth. The facial fossa (depressions) very deep in Merychippus line. Branched into at least 19 grassland species.

Parahippus

32-11 MYA

Parahippus was the size of a modern pony with facial features similar to modern horse.

It carried most of its body weight on its center toe, helping it to run faster.

Kalobatippus*

24-19 MYA

Kalobatippus name means “stilt-walking horse” and had unusually long legs.

It’s legs allowed it to live by eating leaves from trees.

*Scientific illustrations or depictions do not exist at this time.

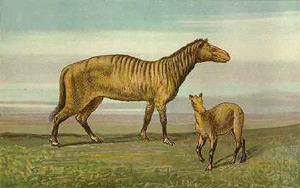

Mesohippus

40-28 MYA

Mesohippus name means “middle horse.”

This horse lived in a drier climate and survived by evolving stronger legs to run fast in open areas and escape predators.

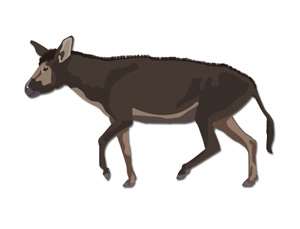

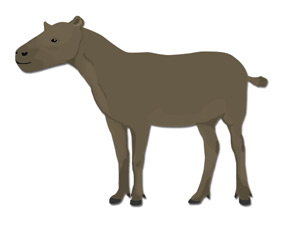

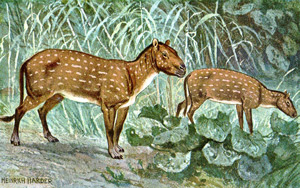

“Hyracotherium”

56-45 MYA

There were many species of “Hyracotherium” or “dawn horse.” It was quite small in size from a Siamese cat to medium dog.

One of the fastest runners of its time but slow compared with modern horses.

It had feet with several small hooflets, a more flexible leg rotation and much shorter leg bones than the modern horse. Lived on fruit and foliage rather than grass.

This state has supplied many pieces of the puzzle that help form the picture of changing climate and habitat, and its relationship to horse evolution.

Though some have been found in nearby Wyoming, so far Nebraska’s fossil record lacks specimens of the earliest horses. However, paleo sleuth Mike Voorhies discovered a deposit of sediment from the early Eocene in Knox County, Nebraska. This small deposit included "Hyracotherium," the earliest horse genus, though not the earliest species. The find is the only evidence in Nebraska of the lush early Eocene forests that grew from 66 to 45 MYA. Historical work was done here by paleo sleuth O.C. Marsh as well as by Mike Voorhies.

At Toadstool Park, a site with specimens from the late Eocene and Oligocene (about 37-28 MYA), primitive horses have been found -- only low-crowned browsers who ate leaves. There are no high-crowned grass eaters. All mammals that lived there are long extinct. It was warm and temperate in the late Eocene but drier and more open in the Oligocene. Historical work was done here by paleo sleuths by O.C. Marsh, Erwin Barbour and Mike Voorhies. Joseph Leidy also did work involving specimens from Toadstool Park. Secord, along with graduate student Grant Boardman, has published recent research on the mammal habitats at Toadstool.

At Norden Bridge, a Middle Miocene site from about 14 MYA, the climate at this time was warm and temperate with riparian (river-related) forest along stream channels. It had nearly frost-free winters (indicated by the presence of species like tortoises that could not tolerate long periods of freezing). It was home to both high-crowned horses (grazers) and low-crowned horses (browsers), indicating a mixed habitat. Historical work was done here by paleo sleuths Morris Skinner and Mike Voorhies.

Fossils from five kinds of horses were found at Ashfall Fossil Beds, where many communities of animals perished and were rapidly buried by a cloud of volcanic ash over the course of one to two months. This Middle Miocene site from 12 MYA was nearly frost-free at that time, with warm grasslands and riparian forests. Historical work was done here by paleo sleuth Mike Voorhies.

At Big Springs, a site from the Pleistocene (roughly 1.5 MYA), many large horse specimens (including zebras) have been found. The specimens suggest this was a warm interglacial interval of the Pleistocene (Ice Age). Historical work was done here by paleo sleuth Mike Voorhies. Recent research was published by Secord and his student, Zachary Kita, on the diets and habitats of horses, camels, elephants, and peccaries.