Carrie Barbour's discoveries as one of the first women paleontologists helped put Nebraska on the map as a landscape teeming with prehistoric fossils. Often getting her hands dirty in the field, she was also instrumental in cleaning and preparing specimens for exhibition. You can still see many of her contributions at Morrill Hall today.

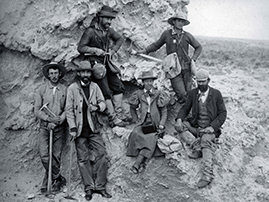

Carrie Barbour (seated center) and Erwin H. Barbour (center left) together with their field crew on the Morrill Geological Field Expedition of 1897, Eagle Crag, north of Harrison, Nebraska. © Barbour Photograph Series, UNL Libraries

Carrie Barbour (seated center) and Erwin H. Barbour (center left) together with their field crew on the Morrill Geological Field Expedition of 1897, Eagle Crag, north of Harrison, Nebraska. © Barbour Photograph Series, UNL Libraries Carrie Barbour came to the University of Nebraska in 1892, taking a position in the Department of Art. Before joining the university, she studied art at Oxford Female College and taught wood carving and china painting for two years at Iowa College in Grinnell. Although she specialized in art and art education, since early childhood, she had shared a passion for natural history with her brother Erwin.

In 1891, Erwin H. Barbour, considered the “Father of Nebraska Paleontology,” was hired as a professor in the University of Nebraska’s Department of Geology and was soon appointed curator of the University of Nebraska State Museum. Seeing that the museum lacked adequate collections, Erwin asked Carrie to assist in his field work and in the preparations lab. Within a year, she left the Art department to focus on her work at the museum. One year later, Carrie became an assistant curator of paleontology—a post she held for almost 50 years.

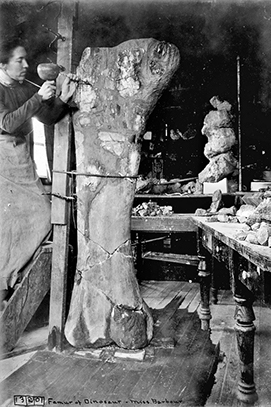

Carrie excelled in preparation work. She painstakingly cleaned and pieced together hundreds of fossils for the museum. She went on many field collecting expeditions, including the Morrill Geological Expeditions of the University of Nebraska and the State Geological Survey. Many of these expeditions were in the Badlands and Black Hills of South Dakota and the Daemonelix beds of Nebraska and Wyoming.

In the summer of 1899, Carrie and an assistant procured more than 20,000 samples of common fossil species such as crinoids, brachiopods, ammonoids, bryozoans, and corals from the Nebraska Carboniferous and Permian formations. Some of these were newly discovered in the state, while several had never before been described.

Carrie Barbour prepares the Apatosaurus femur seen today in the State Museum’s Jurassic Gallery. © Barbour Photograph Series, UNL Libraries

Carrie Barbour prepares the Apatosaurus femur seen today in the State Museum’s Jurassic Gallery. © Barbour Photograph Series, UNL Libraries

In 1912, Carrie Barbour became an Assistant Professor of Paleontology at the University of Nebraska. She held this position for twenty-five years, training Nebraska’s paleo sleuths. As a member of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, at the 1915 annual meeting, she co-presented a paper with Erwin Barbour, “Some Remarkable Sharks’ Teeth from Nebraska,” illustrated by lantern slides. They noted specimens of Campodus that they had collected were better-preserved than any specimens previously discovered. In her expanded role as a professor of paleontology, she defied conventional gender roles to make lasting contributions to the field, particularly in the area of preserving fossil specimens.

Here are just a few of the fossil specimens prepared by Carrie Barbour. View these 3D models and see what she saw:

Carrie was the younger sister of famed Nebraska paleontologist and University of Nebraska State Museum director Erwin Barbour. Both were inspired by their mother Adeline’s passion for natural history. They grew up with three other siblings on a farm in Oxford, Ohio, collecting plant specimens for their mother’s herbarium and making sketches of flora and fauna in the nearby woodland. Encouraged to follow traditional professional pathways, Erwin studied the sciences in college while Carrie studied the fine arts. But Carrie would soon defy tradition to pursue her early childhood passion for the sciences.

When Erwin arrived at the University of Nebraska in 1891, he found the State Museum lacked both direction and quality exhibits. Barbour vowed to build the natural history collection with a series of student expeditions that he would personally fund. The following year, Carrie joined her brother at the museum to work as a part-time preparator. She would eventually leave her position in the Art department to dedicate more of her time to paleontology.

Their work together would often take them far from the university, but one of their discoveries was only a few blocks from the museum. In the fall of 1909, large bones were unearthed by excavators while digging up a cellar on U Street in Lincoln. The owners of the residence quickly notified the Barbours. Carrie and Erwin examined the bones and determined that they belonged to a mammoth! This was the first specimen of its kind to have been found in the city.

Beyond their work at the museum, they also collaborated as artists. Carrie made wood carvings designed by her brother. The two siblings remained close throughout their lives. They corresponded often when they were apart, especially while she vacationed in the Black Hills during the hot Nebraska summers. Carrie Barbour died June 9, 1942.

Barbour would not be the last Carrie in Nebraska to make great strides within the field. Carrie Herbel, the Chief Preparator at the University of Nebraska State Museum, continues Barbour’s legacy by uncovering fossil specimens with modern tools for study and exhibition. As a young person, Herbel found she had an affinity for the natural world. When she studied under Mike Vorhees at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, she discovered a passion for paleontology. That passion has led her to study what she describes as “the best fossils in the world.”

Arnold, Louis B., “The Double Standard in American Science Education: An Historical Perspective.” Journal of College Science Teaching, Vol. 7, No. 5 (May 1978): 292-296.

Arnold, Lois B., “The Barbours: A Family in Paleontology.” Nebraska History 94 (2013): 176-187.

Barbour, Carrie A., “Report on the Work of the Morrill Geological Expeditions of the University of Nebraska University of Nebraska.” Science, New Series, Vol. 11, No. 283. (June 1900): 856-858.

Creese, Mary R. S., and Thomas M. Creese. Ladies in the Laboratory? American and British Women in Science, 1800-1900: A Survey of Their Contributions to Research. London: Scarecrow Press, 1998.