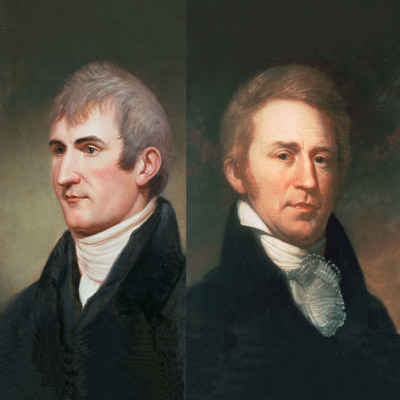

When President Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark across America, no one in the States—or Europe—knew what they would find. Their discoveries defied expectations, debunked myths, and unearthed treasures that would only be fully understood generations later.

Thomas Jefferson trained as a lawyer and became a statesman, but he had an intense interest in natural history. He was fascinated with fossils and what they tell about the past. He studied fossils from New York and Kentucky, including bones of mastodons, mammoths and sloths retrieved from bogs and salt licks. (In fact, the University of Nebraska State Museum has a mastodon tooth that was collected for Jefferson by William Clark in 1807.) He even wrote a paper about a giant fossil claw he studied, presuming that it must have come from an animal of the lion kind, but of most exaggerated size. Actually, the big claw was from a giant ground sloth.

In 1803, President Jefferson negotiated the Louisiana Purchase and commissioned an exploration of the new territory, with documentation of natural history as a major goal. He thought the interior of the continent might be home to exotic life forms such as elephants, lions, and even 'living fossils' (animal species thought to be extinct but actually still in existence). Prior to their expedition, Lewis and Clark were instructed to collect remains of animals and plants, especially those “deemed rare or extinct.”

Fossils had been discovered by Native Americans as well as by early trappers and surveyors. Salt licks and bogs yielded “petrified” remains of mysterious animals. In 1803, Dr. William Goforth had collected several tons of prehistoric bones at Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, which was a salt lick and fossil bed over 15,000 years old. The bones drew the attention of naturalists and roused Jefferson's interest.

To prepare for the Corps of Discovery expedition, Jefferson arranged for Lewis to travel to Big Bone Lick to train with Charles Wilson Peale in collecting fossil remains. (Jefferson was an active supporter of the Peale Museum, which held many “natural curiosities.”)

Lewis and Clark were keen observers. During their mission of exploration, they remembered the bones they had examined and the lessons they had learned while at the excavation in Kentucky.

Lewis and Clark didn't collect nearly as many fossils as they did other specimens. They didn't have the time to search around for embedded bones and dig fossils from solid rock. Some of what they dug up probably deteriorated during travel. Some specimens were sent back during the expedition, but were later lost. For example, a set of specimens was sent back to Fort Mandan and from there to the American Philosophical Society in 1805. From there, the specimens were sent to scientists for study, but were never returned.

Mastodon tooth from Thomas Jefferson's collection from Big Bone Lick Kentucky. © University of Nebraska State Museum.

Mastodon tooth from Thomas Jefferson's collection from Big Bone Lick Kentucky. © University of Nebraska State Museum. Expedition member Sgt. Patrick Gass found a fossil fish jaw. In South Dakota, the Corps also found the backbone of a 45-foot long “fish.” It was later identified as a plesiosaur, an aquatic reptile of the Mesozoic Era. Sgt. Gass's fish fragment is preserved today. Some fossils from the expedition are thought to be among the collections in the Smithsonian. But most of what was collected has been lost.

Like Jefferson, Lewis and Clark thought that the unexplored territory might contain living versions of animals found fossilized elsewhere. And they did find one 'living fossil.' They could tell the bighorn sheep they encountered in the West were the same as one of the unknown animals whose bones they had examined at Big Bone Lick.

It was an age of discovery; the age of science was to come later. Even so, the Corps of Discovery specimens were significant because they raised the visibility of these mysterious animals and served as an eye-opener for the science that would become paleontology.

After the expedition, Jefferson sent Clark back to Big Bone Lick to search for fossils, and Clark unearthed a mastodon tooth along with many other specimens that Jefferson was happy to receive and examine.

Following the work of the Corps of Discovery, Joseph Leidy entered the scene. Leidy was the father of American paleontology, the first great scientist in America. He provided a scientific description of virtually all of the fossils found in North American prior to the mid 1850's. His biography was entitled “The Last Man Who Knew Everything”. It was an apt description of this accomplished scientist.

Leidy described the first fossil collected from the Badlands—the first bone ever found of a new family of mammals known as brontotheres or titanotheres. Alexander Culbertson, a trader, probably found the bone, a partial jaw, and gave it to Dr. Hiram Prout, who sent it on to Leidy.

The jawbone caught the interest of Eastern naturalists and paleontologists. Its discovery propelled scientists to explore the unknown regions of the West, starting in the 1850's. Many government surveys were carried out; including the Hayden Surveys of 1852 and 1857, and it was Leidy who described their extensive collections.

Sadly, with the opening of the Western fossil fields, paleontologists and friends O.C. Marsh and E. D. Cope became bitter rivals in what would be called the “Bone Wars”, each striving for the latest and greatest discoveries. This competition was so distasteful to Leidy that he turned away from paleontology completely.

Name That Fossil

Examine each image and then click on the image to find out if you're right.

Which is a fossil? Is either one a fossil? Are they both fossils?

This is a fossil tortoise.

Some fossils are easier to recognize than others.

You might be looking at a fossil if:

The more you know about the different types of fossils, the better you’ll be as a paleo sleuth. Just remember to get permission to search and/or collect specimens. Collecting fossils on public land is illegal without a permit.

This is a septarian concretion or nodule. It's not a fossil.

A concretion is not a fossil itself. Some call concretions pseudo fossils.

This type or concretion was formed 50 to 70 million years ago when volcanic eruptions caused dead sea life to chemically attract to sediments and form mud balls. When the oceans receded, the balls dried and cracked.

There are many types of concretions. Some resemble eggs or spheres. Sometimes a concretion is formed around an actual fossil.

President Jefferson had hoped that in the vastness of the new territory, Lewis and Clark would find massive creatures such as elephants roaming the countryside. Of course, they never did, but in the winter of 1804, Lewis wrote, “On the south side of this river (possibly the the Osage) 30 leagues below the Osage Village, there is a large lick, at which some specimens of the bones of the mammoth have been found; these bones are said to be in considerable quantities but those which have been obtained as yet, were in an imperfect state.” It would fall to later paleo sleuths to uncover the full story of the mammoths in America.